Recently, “trigger warnings” have sparked controversy after social psychologist Jonathon Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, the director of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, published “The Coddling of the American Mind” in The Atlantic.

This article argued against the use of trigger warnings in academia and suggested that their prevalence may be related to the rise in mental health issues among college students. Trigger warning supporters have refuted these claims.

According to Dictionary.com, a “trigger warning” is defined as “a stated warning that the content of a text, video, etc., may upset or offend some people, especially those who have previously experienced a related trauma.”

It is difficult to impose a blanket rule on such an intensely personal issue. As such, many argue that no one, apart from the survivor, should decide what does and what does not trigger a response to traumatic content.

In fact, when those who have not suffered from a specific trauma insist upon warnings for those who have, it might end up causing more harm than good. Books deemed trauma-inducing have been banned and can lead to discipline and even dismissal for the instructor. These consequences can occur even if the book, once thoroughly examined, does not actually violate its assigned trigger.

Lukianoff and Haidt also argue that trigger warnings are ineffective. The National Center for PTSD does not mention “trigger warnings” as a source of help for trauma. Instead, the Center recommends cognitive behavioral therapy.

Other forms of treatment include “exposure therapy,” a treatment based on, “the idea that people learn to fear thoughts, feelings, and situations that remind them of a past traumatic event…By talking about your trauma repeatedly with a therapist, you’ll learn to get control of your thoughts and feelings about the trauma.” Other options include group therapy, medication and psychotherapy.

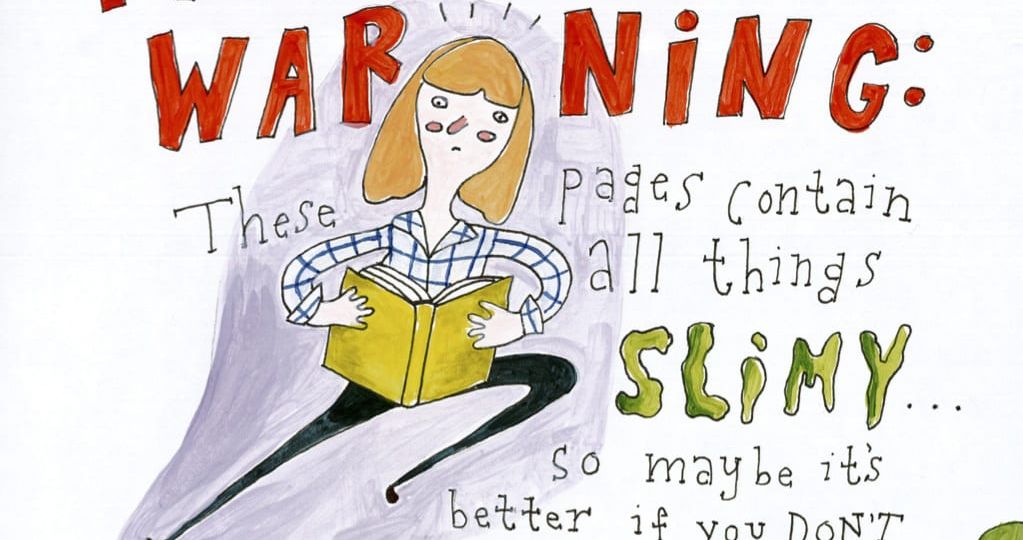

Despite these reservations, trigger warnings continue to spread. The very nature of the warnings is increasingly questionable. The newest triggers, such as “slimy things,” “insects” and “needles” are less relevant and trivialize the complexity of the original topics. One Tumblr site, “Privilege 101,” documents questionable trigger warnings from across academia.

“Discussions of -isms, shaming, or hatred of any kind (racism, classism, hatred of cultures/ethnicities that differ from your own, sexism, hatred of sexualities or genders that differ from your own, sex positive shaming, fat shaming/body image shaming, neurotypical shaming).”

Translation: no discussions of world history, women’s suffrage, Supreme Court cases and certainly no Great Expectations or Pride and Prejudice. Given such a wide-ranging list of triggers, it is easy to see why some professors might be nervous when assigning class material.

To their credit, trigger warnings do seem to work when carefully applied, rather than carelessly attached to every buzzword. This care requires context. Troubling subject matter might be a historical remnant that informs us about deeply entrenched stereotypes and prejudices from the past. In fact, for certain triggers such as death, working through them without a warning may be the most helpful thing a student could do.

According to Viktor Frankl, the inventor of Logotherapy and an existentialist who survived several Nazi concentration camps, “If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death … It may remain brave, dignified and unselfish… Here lies the chance for a man either to make use of or to forgo the opportunities of attaining the moral values that a difficult situation may afford him.”

As someone who has lost nine family members and friends due to heart attacks, cancer, a plane crash, old age and accidents, I have been comforted by books that forced me to confront the grieving process through the loss of a character. Everything I felt, the world appearing too radiantly bright to be real or the desire to crumple to the ground and not move until I had cried it all out, the protagonist felt too and we processed it all, together.

And while what works for me might not work best for everyone, to deny someone in mourning a channel of potential comfort based on a personal perception of their grief seems counterproductive and not worth a warning label to scare them away.

Trigger warnings themselves are not inherently the issue. The issue is their transition from a careful case-by-case application to a blanketing of all disciplines that creates distrust in academic dialogue. I do believe that certain triggers, such as sexual assault, warrant some sort of warning out of courtesy, but, ultimately, we should also be more discerning and stop using seemingly arbitrary triggers like “slimy things.”