Over this summer, an African-American consultant flew from Boston to my hometown of Lagos, Nigeria. He was very vocal in recognizing the degrees of difference when considering infrastructure development or efficiency of the places he stayed. As a consultant, this is what he was paid to do — recognize flaws and speak about what would make the system better. The interaction with the consultant prompted me to write this article, in which I highlight how I have held people to a standard of my background, a background of privilege, and how this may distort the view we have of our “others.” When referring to “others,” I mean those who are different from us in terms of privilege; privileges that can then be the subsidies we each get in life. It is, therefore, important to keep said subsidies in mind as we think of the “others.”

At times we should ask: Could we have lived without this subsidy? For many students on campus, including myself, it is with help from generous donors, hardworking parents and the wizards in our financial aid department that we can converge in Stav Hall, attend courses of our choice and be members of a community with a $500 million-plus endowment. We make it a point to be multi-faceted while finding ourselves in a $63,000 private community.

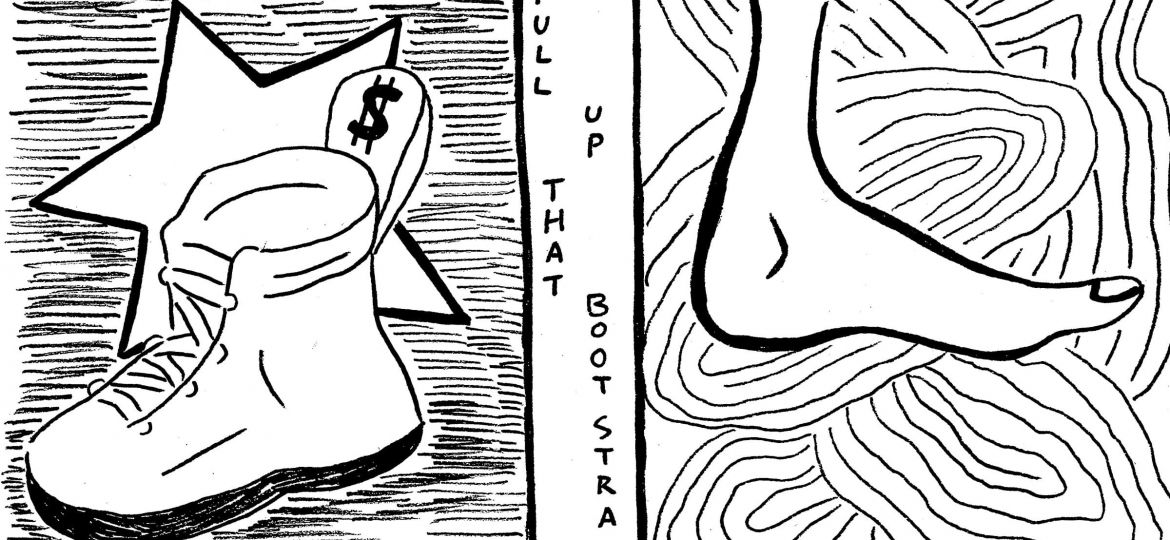

Of course, it is not only through the might, sweat or class of our family that brought us here. It is also not through munificent persons that we were transformed into St. Olaf students. We had to be diligent students in high school, and we each went through the painstaking ritual of the Common Application. And of course, we each sold ourselves to the admissions team. We should recognize and laud our efforts that brought us here; it truly is no small act. We have “picked ourselves up by the bootstraps.”

I believe that it is through this feat from our individual selves that we have become desensitized to those who do not appear to grip the proverbial bootstrap. Let us think of these outcasts first. In Lagos, Nigeria, we have those who sell basic amenities on the road and those who are persistent in washing the windshields of your car. There are many who have forged an elaborate story of why their predicament is not their own fault, and why a small donation would make the day better.

I grew up learning to not look these people in the eyes, to ignore and pass on by. Don’t believe their stories, they will just use your money to buy ogogoro (palm wine) or drugs. This statement alone shows how we think of such people as destitute with no future other than alcohol or drug abuse, this thinking criminal of us.

On my way back home from school when I was 11, I saw a man, unwashed and naked, standing on the road. I wondered why he would be there to make such an unpleasant spectacle, and then I turned my head away just like I had been taught. I became better at not noticing such people.

The greater question I could not answer was: what has made me different from this man? How could it be that I found myself, at age 11, sitting in the back seat of an air-conditioned car, trying to ignore this man who belonged to a different economic background? Was it that he did not have the same support system I had — one with working parents? Or the fact that I, as a scholarship recipient returning from school, was proof that regardless of economic power, there was asymmetrical information in my favor?

We can each think of the privilege we hold as members of an exclusive environment such as St. Olaf. Whether we are paying tuition in full or receiving scholarships and financial aid, we must recognize ourselves as the emerging bourgeoisie, which is why we join a $60,000 per year institution. Besides “bettering” ourselves, I believe this contributes to the growing distance between us and those who do not hold the same cards.

I argue that anyone I am no more an individual than the “other.” To be dealt the same cards as the naked man would make it very difficult for me to find myself in Buntrock Commons, or even to make it through customs here in the States.

Maybe I blame Marx for writing extensively on the power of the proletariat and laments on the consensual exploitation of workingmen, but not writing enough about Friedrich Engels, his munificent person. From his writings, we think of hegemony and complicity of the proletariat. But we must never forget this situation of ours is one of privilege and we must continuously strive to recognize each persons’ value, but not in terms of the camera obscura “other.” This is a call to remind us to appreciate – but never forget – the many subsidies which have brought us here.

Folarin Bandele ’21 (bandel2@stolaf.edu) is from Lagos, Nigeria. He majors in sociology/anthropology.