The 2020 Iowa Democratic Caucus was a well-known disaster. Results came in late, data was inconsistent and confusion reigned. Definitive numbers were not released until three days later than the party had promised and Pete Buttigieg declared victory before the chaos had been sorted out. In short, it was a mess and a highly visible one.

The Iowa caucus is a critical part of the primary season. Early primaries like Iowa, as well as New Hampshire and South Carolina, inform candidates and voters alike on the viability and popularity of candidates, starting the formal process of nominating a contender for the general election. Al Gore, John Kerry, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton all won in Iowa before becoming the Democratic candidate for president. Like it or not, Iowa is important.

The high-profile nature of the caucus has many people, from candidates to journalists, wondering what went wrong. A series of strategic errors and technological issues contributed to the fiasco. At the center of the disaster is an app that was rolled out for the first time for this caucus. It failed and so did its backup plan. Despite reassurances from the state party chair Troy Price, the app designed to make caucusing painless turned out to be anything but simple.

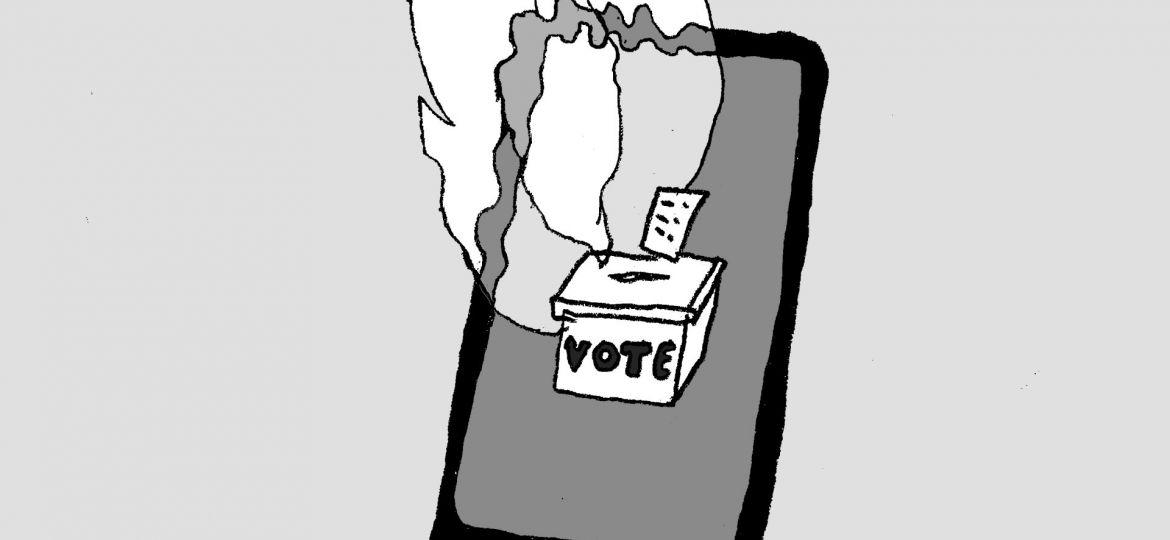

The app’s failure has re-established questions about the entire concept of digital voting. Is it worth the risks? I have heard the stories from parents and professors about the confusion that paper ballots can cause – the 2000 presidential election and its “hanging chads” are testament to the risks involved. Digital voting would also substantially decrease the time, effort and papercuts involved in counting votes. In theory, it also reduces the chance of mistakes and miscounts.

But as Iowa was so kind to demonstrate, digital voting has its flaws too. Technology can fail; technology can be hacked. Admittedly, a number of factors beyond the app are at fault in the case of the Iowa Democratic Caucus. It was a perfect storm.

In the future, we must roll out digital voting in a slower, more systematic way. Thoroughly test the technology. Teach the polling place workers how to use it. Give the designers adequate time and resources to make the best digital voting devices possible. Have a functional backup plan.

If this sounds like a pipe dream to you, you are not alone. There is no viable way to create, test and distribute digital voting technology in time for the general election in November. Even if we take 2020 off the table, it would fall to individual states to manage the rollout, which poses an entirely different set of problems. Any kind of digital voting device would need upkeep and updates to change as technology changes. None of that is cheap or easy.

Digital voting has its upsides –that much is undeniable. But I do not think the benefits are worth the risks. For all their inconvenience, paper ballots have thus far proved immune to bugs and viruses. No one has figured out how to hack paper.

Election security and accuracy are serious concerns for any democracy. If we cannot figure out a way to safely transition to digital voting, sticking to paper may be our best option.

klinef1@stolaf.edu

Grace Klinefelter ’23 is from Omaha, Neb. Her major is Spanish.