Name two XFL teams. No? Name one city with an XFL team. No? Tell me what XFL stands for. Wrong. Trick question. It stands for nothing. Look to it for any meaning at all and you will come up short.

We can really only take one lesson from the existence of the XFL. In 2001 the WWE, an organization which specializes in theatrical circuses parodying a fake sport, and NBC, a foundation dedicated to ensuring Americans are able to see as many advertisements as possible during their short and miserable lives, came together to answer modern society’s most pressing question: what if there was more football after the Super Bowl. What if the football didn’t stop. They thought it would be pretty cool if it didn’t.

A lot of people did not think it was all that cool, and so the XFL played one season and promptly went bankrupt. In 2018, XFL founder Vince McMahon decided this was a big fluke and reunited Dwayne Johnson with his ex-wife Dany Garcia, to re-found the XFL with play to begin Feb. 2020. It turns out Feb. 2020 was a bad time to be getting into the business of slamming men into one another before large crowds. Now, three years later, the XFL is rising from the ashes for its first full season. You probably didn’t notice.

The XFL’s inaugural game attracted roughly 1.5 million viewers. For contrast, the least-viewed game of the 2022-2023 TV-broadcast NFL season was a Monday-night 7-41 Titans Bills blowout broadcast at the same time as a Vikings-Eagle showdown; it drew eight million viewers. A steep drop-off into the second week has put the XFL’s viewership in the same neighborhood as a good MLS game. You know, the MLS? American soccer?

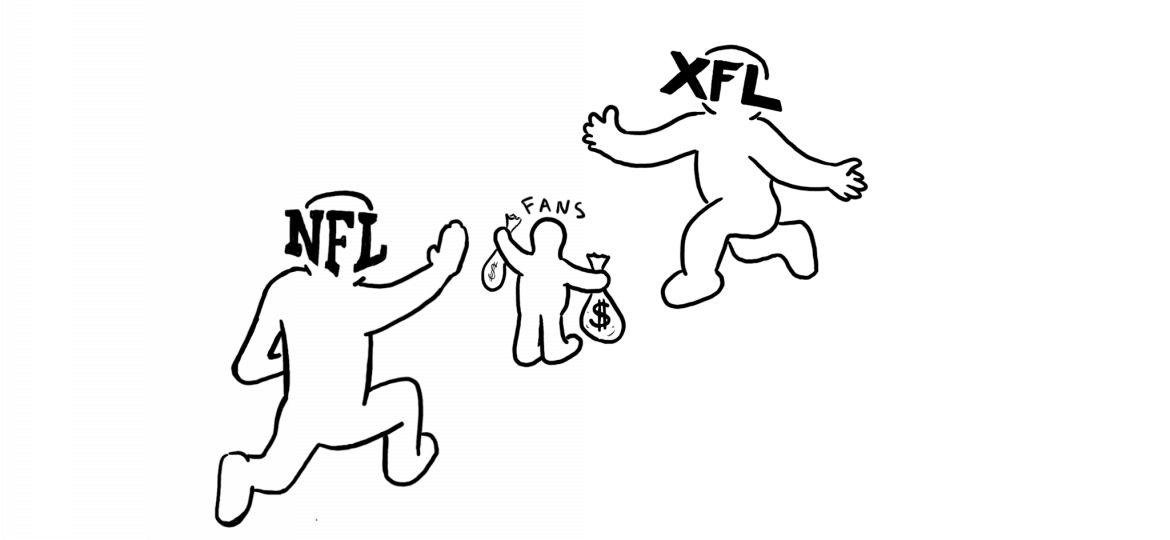

I hate to say all these cruel and true things about the XFL, because millions of Americans and I share a basic philosophy with the league, which is that American professional sports seasons are too short, too buttoned-up, and not all that interesting. Americans are confronted with a small number of teams which are locked into monopolistic leagues hellbent on squeezing money out of unshifting markets that produces constant tension and frequent hatred between fans, players, and team owners. American sports presents itself, and is, more like a smattering of corporate brands we can arbitrarily swear allegiance to, rather than as intangible cultural possessions of communities and places. The XFL does not change this, and is instead precisely the kind of profit-driven, highly corporate sports venture that the NFL embodies. Its problem is only thinking it can play the same game as the NFL and survive.

Residents of the UK have, on a per-capita basis, three times more premier league teams than Americans do NFL teams. The largest sport in terms of teams in North American is baseball, with 236 teams if you count the lowest depths of the minor league. The English football system holds almost 100 for a population less than one-fifth of the United States’. England has no XFLs. When, in 2021, the greatest clubs in European soccer proposed to create a super-league to rival the NFL in corporate shlock, the backlash was so enormous that the league dissolved in weeks. Long seasons, local clubs, and the constant drama and feedback of the relegation system have produced a European sports ecosystem that has stood the test of time. If Americans want to think about ways to mix up their sports leagues, it wouldn’t be a mistake to look to this athletics of terroir, one where small cities and towns are not forced to kowtow to big cities’ franchise-attracting markets and where teams exist independent of the locales whose names they plunder. It would not be a mistake to consider doing the opposite of the XFL.